When researchers and policy makers ask health-related questions they often have to rely on self-reported rather than tested health data. We analysed how reliable this subjective information is and found that misreporting health is associated with a participant’s age, education and country of residence. Men and women, however, cheat equally.

Europe’s population is ageing, making the health of older adults a major priority. Policy makers as well as public and private healthcare providers need to understand how healthy the older population is to, for example, plan future healthcare facilities. Knowing about the physical and cognitive functioning of older adults is also important when reconfiguring pension systems, especially when increasing the retirement age.

Information about the health status of a large population is often based on self-reports, for which individuals are simply asked to tell an interviewer their perceived health status. Tested health data on the other hand, requires a trained interviewer or a health professional such as a nurse to collect data through, for instance, blood samples or cognitive and physical performance tests. Next to higher costs, these procedures also require more time and effort than simple questionnaires, which is why self-reports are more readily available than performance tested health measures.

Self-assessed vs. tested physical and cognitive health

In a recent study we explored how reliable these self-reported data are. More specifically, we analysed when it is feasible to use subjective health data to compare demographic groups and when, instead, we should rely on tested health information. To that end, we compared self-assessed health data from the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) with their tested equivalent. To evaluate reporting behaviour with regard to physical health, survey participants were first asked if they had difficulties in getting up from a chair. Following this subjective assessment, participants were asked to physically stand up from a chair allowing us to identify whether there was a difference between the self-reported and performed mobility of the person. We also used a similar approach to see how accurate individuals report their cognitive abilities – in SHARE, participants were first asked to self-rate their memory and then performed a memory test by recalling a list of ten words. Comparing self-assessed with tested health allowed us to not only identify discrepancies, but in fact we assessed if an individual overestimated his or her health, underestimated his or her health, or achieved concordance between the performance tests and the self-assessments.

Who is telling the truth about their health?

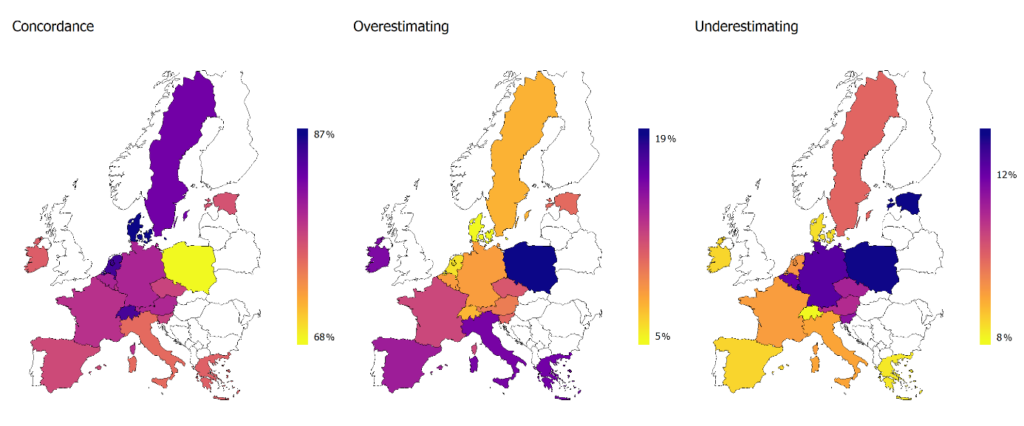

We found large differences in reporting behaviour between European countries, which indicates that one has to be careful when comparing the health of countries based on self-assessed data. Southern as well as Central and Eastern Europeans are much more likely to misreport their physical and cognitive abilities than Northern and Western Europeans (see Figure 1). Furthermore, Southern Europeans seem particularly prone to overestimate their health. In Italy, for example, only 19.4% of respondents reported to have difficulty getting up from a chair, while, in fact, 24.1% were unable to stand up when they were asked to do so in the test.

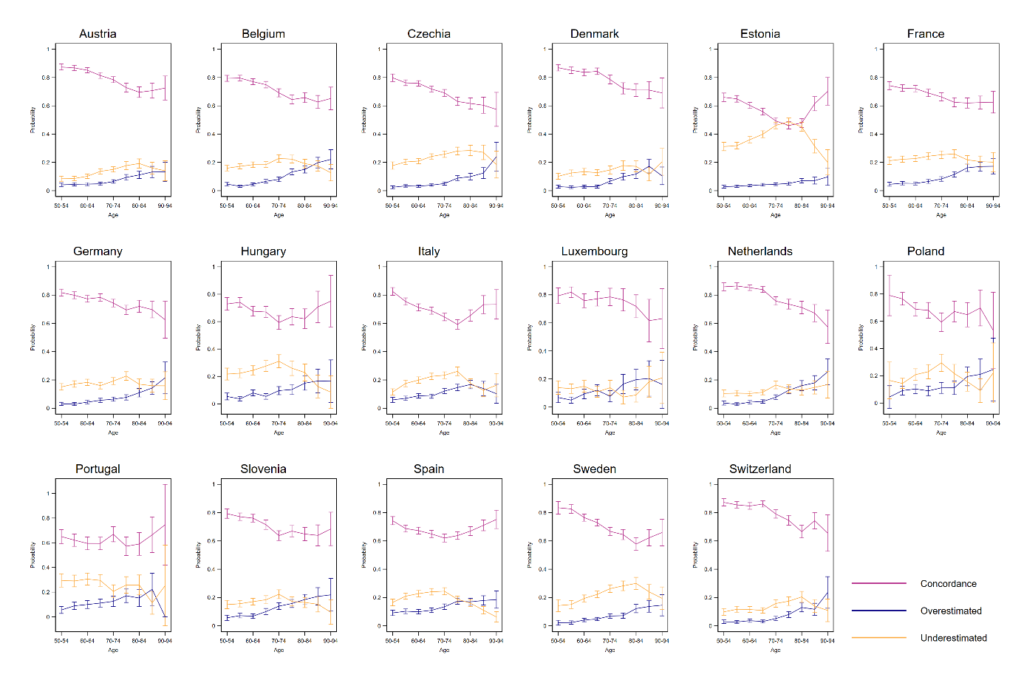

We also found that older individuals are more likely to misreport their health. While 85.5% ‘get it right’ in the age group 50-54, only 65.6% ‘get it right’ in the age group 90-94. In short, older individuals are particularly prone to overestimate their health (see Figure 2). This makes it difficult to compare self-reported health of older individuals to that of younger individuals. The large variation in reporting style between age groups can partly be explained by differences in employment status – Individuals that are working are more aware of their health status and younger individuals are more likely to be employed than older individuals.

Overall, highly educated individuals achieve higher concordance when assessing their own health status than less educated individuals. This finding might be related to the generally better health literacy of higher educated people. Other studies have also shown or speculated that women report their health differently to men. We also found some differences between genders, but they were not very large. This indicates that women ‘cheat’ as much as men do when it comes to their health, at least for the health dimensions that we looked at.

Lessons learned

In summary, self-assessed physical and cognitive health has to be treated cautiously, especially when comparing health across countries, age and educational groups. However, we want to emphasise that self-reported data can still be a valuable source of information for policy makers and researchers if the data is treated and interpreted with care.

About the authors:

Sonja Spitzer, Population and Health Economist working at the Vienna Institute of Demography as well as at the World Population Program at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria

Daniela Weber, Assistant Professor in the Health Economics and Policy division at the Vienna University of Economics and Business and Research Scholar at the World Population Program at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria

This article is based on:

Spitzer S. & Weber D. (2019): Reporting biases in self-assessed physical and cognitive health status of older Europeans. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0223526. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223526

Leave A Comment