Just like the body, our mind ages as well. The principal faculties of our mind, cognitive functions, include the ability to remember, plan and reason and are crucial to maintain throughout the life course so we stay independent in old age as long as possible. Every individual´s mind ages at a different pace. The question, why some older individuals maintain their cognitive functions and some not, is of great interest and can give clues how to tailor preventative strategies in order to protect cognitive functions.

A growing body of evidence has pointed out that cognitive ageing has its roots in the socioeconomic environment where we grew up as children. For example, several authors have suggested that people that come from poverty have lower cognitive abilities and may be more likely to develop dementia. This can be explained by several mechanisms: First, a good socioeconomic situation in childhood provides sufficient positive stimulation and shapes the developing brain so it tolerates more pathology before it reaches the threshold for manifestation of cognitive problems (hypothesis of passive cognitive reserve). Second, older individuals that come from richer environment could actively use compensatory processes so they could slow down their cognitive decline (hypothesis of active cognitive reserve). Third, the poor socioeconomic environment in childhood may set an individual on a pathway towards low education and unhealthy life style habits, leading to cardiovascular disease, depression and socially isolated life, which are all associated with cognitive problems (hypothesis of life style factors).

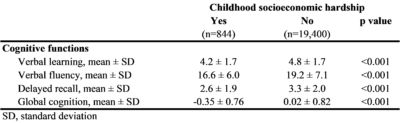

To find out, which of these three mechanisms play the biggest role, we examined data on 20 244 people from 16 European countries who were part of the Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). To determine cognitive skills, participants were given tests that measured verbal and memory skills, like being able to name animals, learning new words and recall them after a delay. To determine socioeconomic position in childhood, participants were asked questions about the conditions of their households at age 10, using a method known as a “life history calendar,” a technique used to improve the accuracy of recalled information. Questions included the number of rooms, the number of people living in the home and the number of books in the home. We calculated a ratio for the number of people in the home to the number of rooms and considered persons with the highest ratio and the lowest number of books as those having experienced socioeconomic hardship.

Table 1: Cognitive function and childhood socioeconomic hardship

How can these findings be interpreted? This study shows that the environment where the individuals grew up was mirrored in the level of cognitive skills in older age, and this was only partly explained by education, depression or different life style factors. However, the childhood socioeconomic environment no longer affected how the people fought against the declining skills as they aged. This supports the hypothesis of passive cognitive reserve and suggests that childhood socioeconomic position is unlikely to influence the rate of cognitive decline in older age as advantages from childhood environment do not have effects on counteracting age-related pathology. We believe that the focus of strategies aiming to protect cognitive health should be shifted into childhood, taking into account that children facing social and economic challenges should be provided with more resources to counter the disadvantages they face.

About the authors:

Pavla Čermáková – National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany (Czech Republic)

Anna Kagstrom – National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany (Czech Republic)

Tomáš Formánek – National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany (Czech Republic)

Petr Winkler – National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany (Czech Republic)

This article is based on:

Cermakova P, Formanek T, Kagstrom A, Winkler P. Socioeconomic position in childhood and cognitive aging in Europe. Neurology. 2018;91(17):e1602-e1610 https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006390

Leave A Comment