Despite the fact that most grandparents in Europe provide childcare services to their grandchildren, little is known on whether this activity is beneficial or detrimental to grandparents’ mental health. The common perception, as well as the results of earlier studies, lean towards a beneficial effect. Unfortunately, this conclusion is not warranted.

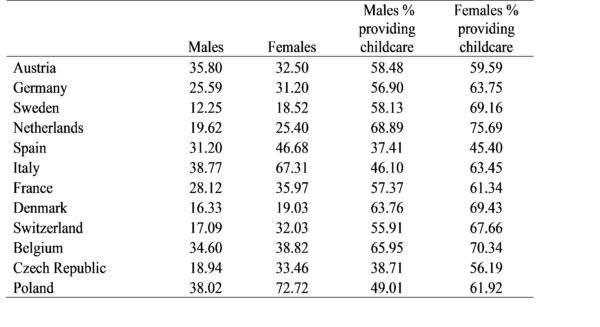

In most families, parents and children are engaged in an intense and continuous exchange, made of transfers and reciprocal help. Parents often support their children either financially or with transfers in kind, even when the latter are grown up. Childcare is one of the most common services supplied by grandparents in Europe (Table 1). Grand-parenting is valuable both individually and socially, because it makes up for the often insufficient supply of kindergartens and formal childcare and because it allows mothers to participate more intensively to the labor market, with important economic benefits. But does child caring benefit grandparents as well?

Table 1. Average monthly hours of childcare, by country and percent grandparents who provide childcare.

Source: SHARE data waves 1 and 2.

On the positive side, care can be rewarding and a source of higher satisfaction, and lead to more physical exercise and mental activity, which improve grandparents’ health (see Silverstein, Giarrusso and Bengtson, 2003; Coall & Hertwig, 2011; Powdthavee, 2011). On the negative side, caring means also responsibility and stress, which may harm grandparents’ health and lead to depression, and also reduces leisure and alternative uses of time (see Minkler, 1999). The balance of positive and negative effects is not clear a priori. The early literature in this area has focused on grandparents who are primary caregivers of their grandchildren, because parents are absent. For instance, in the U.S., Baker & Silverstein, 2008, have found that grand-parenting is associated to poorer health, lack of privacy and leisure time, a heightened risk of isolation, and depression. Clearly, providing care on a supplementary rather than on a primary basis charges grandparents with less responsibility, especially about key decisions in children life, such as education and their other activities. Di Gessa, Glaser and Tinker, 2015, among others, find that grandparents experience some health benefits, independently of the intensity of care. This positive association, however, could simply reflect the fact that grandparents in better health are more likely to be engaged in childcare.

We estimate the causal effect of grandchild care on the depression of grandmothers and grandfathers aged between 50 and 75 years who provide childcare on a supplementary basis, using data from the Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE).

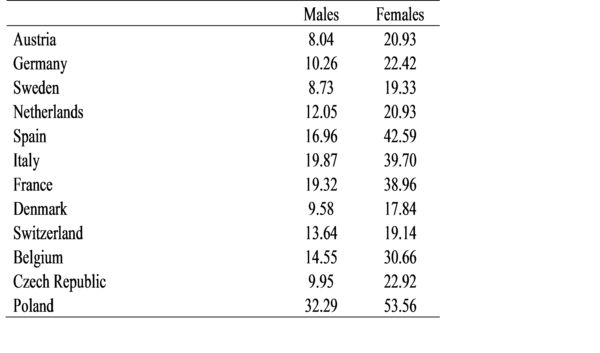

Depression is widespread in Europe (Table 2), it is the second leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the burden of suicide and ischemic heart disease (Ferrari et al. 2013). It is a syndrome characterized by the presence of specific symptoms, including anxiety, insomnia, fatigue and a number of psychosomatic disorders, that can be triggered by biological, psychological and socio-economic factors, such as negative life events, stress and high psychological strain (high psychologic demands and low decision authority) (Mausner-Dorsch and Eaton, 2000).

Table 2. Percent depressed (the index Euro-D is equal to or higher than 4), by gender and country.

Source: SHARE data waves 1 and 2.

Since the allocation of grandparents to childcare is unlikely to be random, but depends instead on individual characteristics, the identification of causal effects, rather than simple associations, requires a source of independent variation in the provision of childcare, that is called an instrument in econometrics. Intuitively, an instrument triggers a chain of causation by producing an independent variation in childcare. Any resulting variation in depression can be attributed to the variation in childcare and corresponds to the causal effect of childcare on depression.

The independent source of variation that we exploit in our study has to do with the fact that the date of interview in SHARE is as good as randomly determined. Hence, two grandparents equal in all respect, included the date of birth of their grandchildren, will have grandchildren of marginally different ages when they are interviewed. Grandparents interviewed later will have marginally older grandchildren than grandparents interviewed earlier. Since childcare declines with the age of grandchildren, it follows that grandparents interviewed later will provide less childcare than grandparents interviewed earlier.

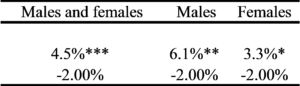

Our estimates show that childcare has a positive and statistically significant effect on depression. The estimated effect is sizeable: we find that ten additional hours of childcare per month increase the probability that grandmothers and grandfathers develop depressive symptoms by 3.2 and by 6.1 percentage points respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Effect of increasing childcare by 10 hours per month on the probability of being depressed. Full sample and by gender.

Source: Standard errors in parenthesis. One, two and three stars for statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent level of confidence. Our estimates based on SHARE data waves 1 and 2.

These effects are produced by those grandparents who alter their provision of childcare in response to a marginal increase in their grandchildren age. However, not all grandparents react with the same intensity. Those who react more are overrepresented among grandparents who provide intensive childcare and use a sizeable proportion of their time to look after their grandchildren. Second, they are more likely to have higher than median household income and few children. Third, they are more likely to live in Southern and Eastern Europe (Italy, Spain and Poland), where activity rates are lower and the intensity of informal childcare is higher than in Central and Northern Europe.

Our findings suggest that the negative effects of childcare on the mental health of grandparents more than offset the potential benefits, and that males suffer significantly more than females. To further investigate these effects, we decompose depression into two main factors, called in the literature affective suffering – which includes depression, tearfulness, wishing death, lack of sleep, guilt, irritability and fatigue – and lack of motivation, which includes pessimism, lack of enjoyment, interest and concentration, and find that childcare affects both factors for grandfathers but only lack of motivation for grandmothers.

The importance of healthy ageing cannot be understated for the rapidly ageing populations of Europe and especially Southern Europe. Preventing depression in the senior population should be a key concern, because depression is a risk factor for other diseases and a leading contributor to disability. Our results indicate that grandparents would benefit from policies that favor the expansion of formal childcare, parental care and alternative forms of informal care.

About the authors:

Giorgio Brunello, Department of Economics and Management, University of Padova, Italy.

Lorenzo Rocco, Department of Economics and Management, University of Padova, Italy.

The article is based on:

Brunello, G. & Rocco, L. Rev Econ Household (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9432-2.

Leave A Comment