Grandparenthood plays an important role in an individual’s later life. We studied the relationship between older people’s subjective wellbeing and having grandchildren, their number and provision of grandchildcare. Grandparents reported higher satisfaction with their lives compared to grandchildless. However, overall, it is the provision of grandchild care that positively benefits grandparents’ wellbeing rather than having grandchildren per se.

The article “Grandparenting, education and subjective well‑being of older Europeans”, forthcoming in the European Journal of Ageing, examined the role of grandchildren for grandparents’ subjective wellbeing (SWB). We used SHARE data from 52,726 women and 42,868 men aged 50 to 84 from 20 countries.

We studied whether having grandchildren, their number, and the provision of grandchild care matter for older people’s subjective wellbeing. Subjective wellbeing was assessed in terms of self-reported satisfaction with life. We also considered to what extend the effect of grandparenthood varied by gender, educational level and across different countries.

Our analyses indicate that grandparents are, on average, more satisfied with their lives than grandchildless people, especially if they have 3 or more grandchildren. However, this “grandparenthood effect” is mainly driven by whether grandparents provide or not care to their grandchildren. Indeed, grandparents who never look after their grandchildren are less satisfied with their lives as compared to their grandchildless counterparts.

Overall, we found no striking differences by gender in the association of grandparenthood with life satisfaction. The only noteworthy discrepancy refers to the fact that grandmothers, in most countries, report higher gains in terms of life satisfaction compared to grandfathers when they provide grandchild care. This result might be driven by the fact that grandmothers are usually more socially expected to provide care to their grandchildren, thereby perceiving lower costs and more rewards associated with such a role.

Education did not modify the association of grandparenthood with life satisfaction. On the one hand, grandparents with higher levels of education may be more likely engaged in a variety of social activities, thereby reducing the relative importance of the role of grandparenthood on life satisfaction or even increasing the costs associated with caregiving. On the other hand, higher educated people may have more (economic and cultural) resources and this may reduce possible stress due to (high intensity) caregiving. The fact that we did not observe relevant differences in the association between grandparenthood and life satisfaction by level of education may indicate that these two opposing mechanisms compensate each other.

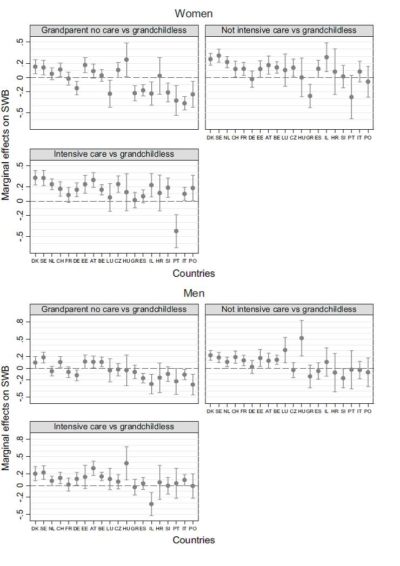

Fig. 1 Marginal effects of having grandchildren and providing intensive (i.e., at least weekly) or not intensive (less often than weekly) grandparental childcare on SWB, by gender and country.

Note: Marginal effects measure the difference in terms of SWB between two groups in a given country. DK Denmark, SE Sweden, NL Netherlands, CH Switzerland, FR France, DE Germany, EE Estonia, AT Austria, BE Belgium, LU Luxemburg, CZ Czech Republic, HU Hungary, GR Greece, ES Spain, IL Israel, HR Croatia, SI Slovenia, PT Portugal, IT Italy, PO Poland. All the analyses control for age, marital status, employment status, number of children, whether the respondent lives in a rural area; whether the respondent has any long-standing illnesses; GALI; survey waves. Confidence intervals for pair-wise comparisons at 5%. Source: Arpino, Bordone and Balbo (2018)

Comparisons across countries (see above figure) revealed that grandparental childcare (either intensive or not) is generally associated with higher life satisfaction. An interesting finding was that in countries where it is socially expected for grandparents to have a role as providers of grandchild care (e.g., Italy, Poland, and Spain), not taking on such a role is more strongly associated with poorer subjective wellbeing as compared to what countries where formal childcare services cover most of the childcare needs (e.g., Denmark and Sweden).

Overall, our findings supported previous evidence on the importance of social networks and intergenerational contacts for older people’s subjective wellbeing and point to the fact that lacking (kin) networks may negatively influence older people’s satisfaction with life, especially in more familialistic countries.

About the authors:

Bruno Arpino, Department of Political and Social Sciences and the Research and Expertise Center for Survey Methodology (RECSM), Pompeu Fabra University (UPF).

Valeria Bordone, Department of Sociology, University of Munich (LMU), Munich, Germany.

Nicoletta Balbo, Department of Social and Political Sciences and Dondena Centre for Research on Social Dynamics and Public Policies, Bocconi University, Milan.

The article is based on:

Arpino, B., Bordone, V. & Balbo, N. Eur J Ageing (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0467-2

Leave A Comment