Despite the increase in awareness of chronic disease, little is known about whether multimorbidity has had a diminished impact on health in Europe in the past decade. We used multiple cross-sectional data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe to estimate that the prevalence of multimorbidity rose in the period 2006–2015. We also found a marginal reduction of the impact of multimorbidity on primary care visits and functional capacity. Multimorbidity continues to pose challenges for European health care systems, with only marginal improvement on health care use and health outcomes since 2006.

Multimorbidity, which is defined as the presence of two or more coexisting chronic conditions, is highly prevalent worldwide. Its prevalence is estimated to further increase as a result of aging populations, increased exposure to risk factors, and improvements in medical technology. Multimorbidity has been associated with worse physical and mental health outcomes and poor quality of life. The management of multimorbidity poses complex challenges for health care systems worldwide, considering that people with multimorbidity have increased health care use and are at greater risk of unplanned hospital admissions.

Improving outcomes for people with multimorbidity in Europe is challenging. In the majority of European health care systems, clinical guidelines and chronic disease management programs are still organized following a single disease approach and might not be suitable for treating people with multiple chronic conditions, who often require a multidisciplinary approach. Furthermore, chronic disease management programs in European health care systems are often implemented at the local level, with only few cases of integrated care approaches rolled out nationally that target people with multimorbidity. Additionally, integrated care approaches vary in terms of the targeted population.

Despite the increase in awareness and the multiple initiatives in place, especially in some European countries, the management of multimorbidity might still be suboptimal because of the numerous challenges that European health care systems are facing. Little is known about whether recent efforts to improve the management of people with multimorbidity in Europe has had a positive impact on their health care use and health outcomes. Using SHARE data from ten European health care systems, we aimed to estimate the change in the prevalence of multimorbidity from 2006 to 2015 and to assess the modification effect of time on the impact of multimorbidity on health care use and health outcomes.

For the purpose of this study, we used four cross-sectional data panels from wave 2 (2006–07), wave 4 (2011), wave 5 (2013), and wave 6 (2015) of the database. We considered data from ten European countries present in all of the above survey waves: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Our main variable of interest was the number of coexistent chronic conditions reported by each respondent, including: heart attack/problem; high blood pressure; stroke/ cerebral vascular disease; diabetes/high blood sugar; chronic lung disease; arthritis/rheumatism; cancer; stomach/duodenal/peptic ulcer; Parkinson disease; cataracts; hip or femoral fracture; other fractures; Alzheimer disease/dementia/ organic brain syndrome/senility/other serious memory impairment; and clinical depression. Consistent with previous research, we defined health care use as the number of primary care visits (including outpatient clinic visits) and whether respondents had been admitted to the hospital in the previous twelve months. Descriptive statistics and unadjusted prevalence of multimorbidity were calculated using the survey weights provided with the data set. Poisson generalized linear regression models were employed to model the change in the prevalence of multimorbidity over the study period, and prevalence ratios were estimated.

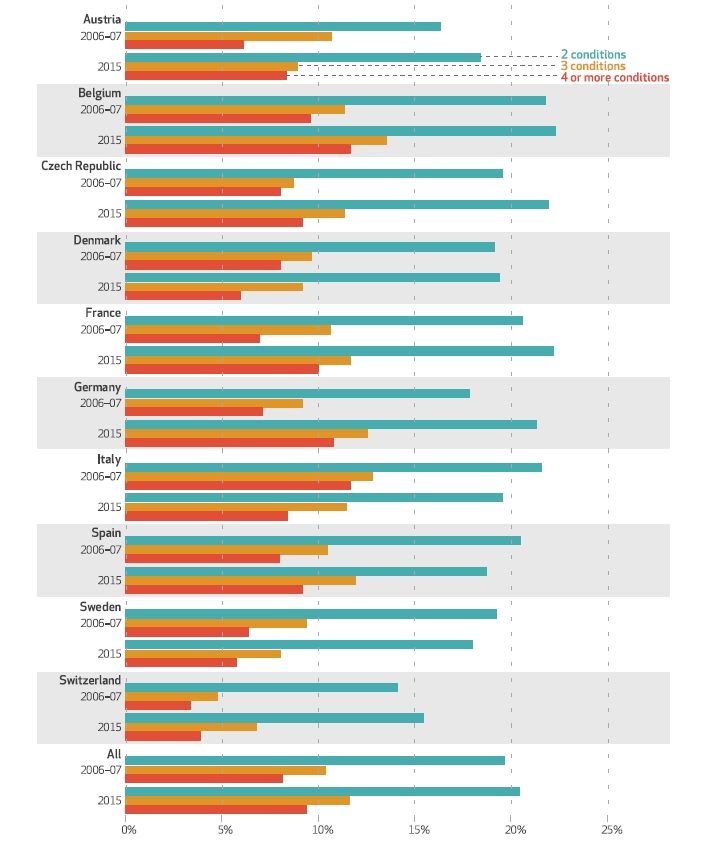

In 2006–07, 31.4 percent of respondents did not report any chronic condition, while 30.3 percent reported one condition, and 38.2 percent reported having multimorbidity. Among people with multimorbidity, the shares of those who reported having two, three, and at least four chronic conditions were 19.7 percent, 10.4 percent, and 8.1 percent, respectively. In 2006–07 Switzerland was the country with the highest proportion of people reporting no chronic condition (46.0 percent) and the lowest proportion of people with multimorbidity (22.3 percent), while Italy had the lowest proportion of people reporting no chronic condition (25.2 percent) and the highest proportion of those with multimorbidity (46.1 percent).

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from waves 2, 4, 5, and 6 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe

Note: Descriptive statistics were calculated using the survey weights provided

We found that multimorbidity was highly prevalent in people ages fifty and older in ten European countries between 2006–07 and 2015. The prevalence of multimorbidity increased from 38.2 percent in 2006–07 to 41.5 percent in 2015, with broadly similar patterns found in individual countries. When we adjusted for confounders, we found the greatest increase in prevalence in Germany, while Italy experienced the greatest decrease in prevalence. Multimorbidity was strongly associated with the use of both primary and secondary care. Over the ten-year study period we saw evidence of reductions in primary care visits in Belgium, the Czech Republic, and Spain, while in Germany a reduction in the probability of hospital admission was found. Increasing numbers of chronic conditions were associated with reduced functional capacity, worse perception of health status, and worse quality of life. Marginal reductions in the relationships between multimorbidity and self-perceived health status were found over time, while there was no change for functional capacity and quality of life.

Our findings suggest that associations between multimorbidity and worse outcomes and poor quality of life remain strong, with improvements only in selected indicators in countries such as Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, and Spain. With aging populations, consequent longer exposure to risk factors, and improvements in medical technology, the increasing prevalence of multimorbidity has become a major challenge. European health care systems have been slow to respond, with care pathways typically fragmented and organized around single diseases. Our findings provide further evidence supporting the need to implement national patient centered strategies to improve care and health outcomes for older people with multiple chronic conditions and the importance of identifying indicators that might be used to monitor the prevalence of multimorbidity and its burden on European health care systems.

The article is based on:

Raffaele Palladino, Francesca Pennino, Martin Finbarr, Christopher Millett, and Maria Triassi. Multimorbidity And Health Outcomes In Older Adults In Ten European Health Systems, 2006–15. Health Affairs Vol. 38, No. 4 (2019): 613–623, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05273 .

About the authors:

Raffaele Palladino is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health, University Federico II, in Naples, Italy, and a PhD student in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, in the United Kingdom.

Francesca Pennino is a research fellow in the Department of Public Health, University Federico II.

Martin Finbarr is a professor of medical gerontology at the School of Medical Education, King’s College London, in the United Kingdom.

Christopher Millett is a professor of public health in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London.

Maria Triassi is a professor of public health in the Department of Public Health, University Federico II.

Leave A Comment