Spouses (and partners) are the most important source of care in old age. There are, however, interesting differences as to whether spouses care alone, receive informal support from other family members or formal support from professional helpers, or outsource the care of their spouse completely. The present article contributes to the literature by differentiating between solo spousal care-giving and shared or outsourced care-giving arrangements, formal and informal care support, and showing how care-giving arrangements vary with gender, socio-economic status and welfare policy.

Against the backdrop of increasing longevity (Eurostat, 2017), the inquiry into the causes of and motivations for informal care also has grown in importance. Spouses and partners are an important source of care and often act as ‘primary care-givers’. Even though many care-related tasks are still female-dominated, men are substantially engaged in spousal care-giving (Bond et al., 1999; Hirst, 2001; Ribeiro and Paul, 2008). Moreover, men’s share of the informal care-giver volume is projected to increase further (Pickard et al., 2007). However, there are marked differences between countries regarding the amount and intensity of informal care provided to kin as well as gender and social equality in the division of such care work.

Despite the importance of the topic, there are only a small number of articles investigating older men’s contribution to spousal care-giving based on representative data, and there are still several research gaps. The first relevant gap in the literature pertains to how care is measured. Second, we cannot rule out that there is more than one person involved in the home-based care of a frail elderly person. Finally, male care-giving has hardly ever been addressed with respect to welfare policy as a driver of or barrier to male engagement in spousal care-giving.

The present article thus aims at closing the aforementioned research gaps by investigating the involvement of men and women in spousal and partner care, as well as its link to socio-economic status and welfare policy. We investigate the circumstances under which men and women act as solo care-givers, decide to share their responsibilities, or outsource them to informal care-givers such as family members or a professional home care service. Moreover, we address the role that socio-economic status and welfare policy play in the choice of care-giving arrangements. In this respect, we investigate how involvement in spousal care-giving varies depending both on the households’ socio-economic status as well as welfare state expenditures on two different elder-care schemes.

Adding to previous research, we compare 17 countries and their expenditures on two elder-care schemes: Cash-for-Care and Care-in-Kind. The empirical analyses draw on the most recent wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) data from 2015.

Based on our results, care-giving within the marital dyad today is still a popular and widely used option for dealing with declining health within a partnership. Of those individuals aged 50 years or older living together with a spouse who receives care, around 80 per cent are themselves engaged in spousal care-giving, and around half act as solo care-givers. However, exclusive long-term spousal care-giving is neither the only option nor the last resort. As couples age together, it is often the functionally less-limited person who provides care for the functionally more limited one. With growing care demands, taking care of a frail spouse alone may become difficult. When the care load is intense, and a care-giver’s health is impaired, the care load is likely to become shared with informal or formal helpers or outsourced completely to a third person.

Besides health, our results indicate that there is a range of other factors involved in the choice of care-giving arrangements, which makes it necessary to differentiate between spousal care-givers further. Spousal care can be split into solo or shared care-giving, and – in the case of shared care – whether care is shared with informal or formal helpers. Deciding on a care-giving arrangement is thus a complex problem which depends on various dimensions of needs and resources of several actors, as well as on family and social contexts.

Men and women seem to choose different care-giving arrangements. While most caregiving women act as solo care-givers, men share care-giving with informal helpers significantly more often, i.e. with family members, friends or neighbours. In that respect, our findings are in line with previous literature. Men’s choice of informally shared care-giving can partly be explained by their higher propensity to be engaged in the labour market. As employment and care-giving compete for time resources, we argue that informally shared care-giving arrangements offer more flexibility to combine work and care-giving than formally shared care-giving arrangements. Financial resources, on the other hand, seem to be less important than time resources.

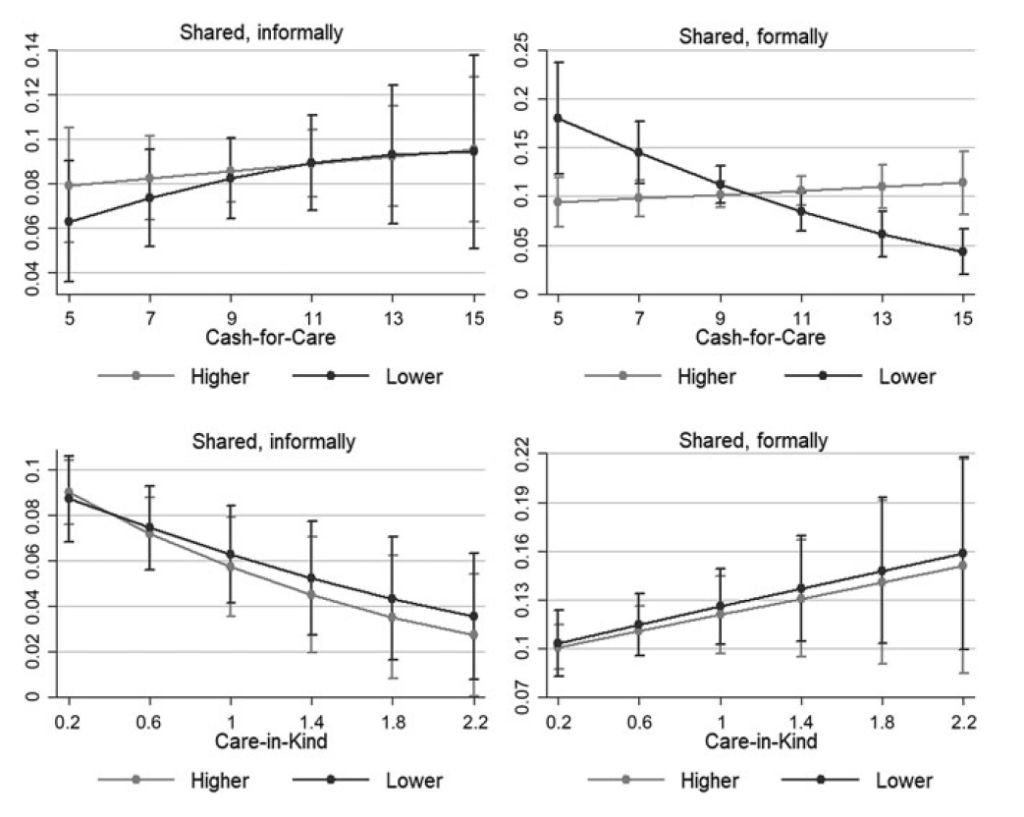

Notes: Capped spikes represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. The x-axis indicates the percentage of expenditure for the respective scheme as a share of total Gross Domestic Product; the y-axis indicates the prevalence of the caregiving arrangement.

Source: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Release 6.0.0, Wave 6; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017)

Besides individual characteristics, welfare policy in the respective country plays an important role, too (see Figure 1). We compare expenditures for two oldage care policy schemes, namely allowances for care-receivers with which they can employ an informal caregiver or purchase services on the market (»Cash-for-Care«) and services, such as publicly provided or financed home care and home help (»Care-in-Kind«). Care-in-Kind measures constitute inclusive measures when it comes to the engagement of spouses as care-givers insofar as they increase the likelihood for caregiving arrangements where the spousal caregiver and a formal service share the caregiving tasks (lower right panel in Figure 1). However, they do, as the lower left panel in Figure 1 indicates, ‘crowd out’ other informal helpers, presumably own children (Brandt et al., 2009). When comparing these effects for low- and high-income groups (dark and light grey lines), we observe that the effect of Care-in-Kind policy does not vary between the income groups. Cash-for-Care schemes, on the other hand, seem to affect the choice for caregiving arrangements differently for low and higher income households. Whereas the likelihood for lower income housholds of choosing a formally shared caregiving arrangements decreases the higher the Cash-for-Care expenditures it slightly increases for higher income households. This indicates that the ‘extra cash’ in the household budget of the frail person and his or her spouse is used quite differently according to one’s socio-eocnomic status. Whereas higher-income households are able to ‘top up’ the received allowances with their own financial resources and purchase formal services, lower income couples may rather use the allowance for other purposes and rely on informal caregivers.

Generally, our article shows the importance of investigating spousal care as a specific form of informal care-giving. To sum up, we conclude that there is large variation in care-giving arrangements chosen by spousal care-givers. The choice of such care-giving arrangements depends on sex, socio-economic status and welfare policy context. Moreover, by contrasting Cash-for-Care and Care-in-Kind expenditures, we were able to show that the impact of policy measures for long-term care on care-giving arrangements varies with socio-economic status and may, thereby, contribute to both reducing or preserving inequalities in old age.

About the authors:

Dr. Ariane Bertogg, Department of History and Sociology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

Prof. Susanne Strauss, Department of History and Sociology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

The article is based on:

Bertogg, A., & Strauss, S. Spousal care-giving arrangements in Europe. The role of gender, socio-economic status and the welfare state. Ageing and Society, 1-24. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001320

Leave A Comment