European countries follow diverse internal migration trends. Some countries have recorded a rise in the proportion of their inhabitants migrating internally while others have recorded stability or even a decline. Reasons underpinning these diverging trends remain poorly understood. We draw on SHARE to explore an overlooked process: the impact of childhood relocations on mobility decisions later in life.

The decision to change region of residence within a country is a complex process to maximise opportunities under a set of resources and constraints. The migration decision process is also shaped by previous migration experiences: the likelihood to migrate increases with the age at first adult migration and the number of past moves in adulthood (Clark and Lisowski 2018, Bernard 2017). These recent findings suggest a path dependency in individual migration trajectories but the impact of childhood mobility has not yet been considered.

We know that migration and residential mobility can affect cognitive and behavioural development in childhood, with consequences on well-being later in live. However, it is unclear from the psychology literature whether childhood relocations should enhance or detract mobility in adulthood. On the one hand, because migration is disruptive to a child’s life, prospective migrants may view migration negatively and be less inclined to move as adults. On the other hand, moving to a new location can provide opportunities and equip children with the skills to handle new social contexts. Taken into adulthood these skills should benefits individuals who may then be more willing to migrate.

To test these hypotheses, we draw on life-histories collected in wave 3 of SHARE and examine the extent to which the timing and number of changes of residence in childhood shape adult mobility behaviour between 18 and 50 years in 11 European countries. We use negative binomial regression models controlling for respondent’s characteristics and those of their parents.

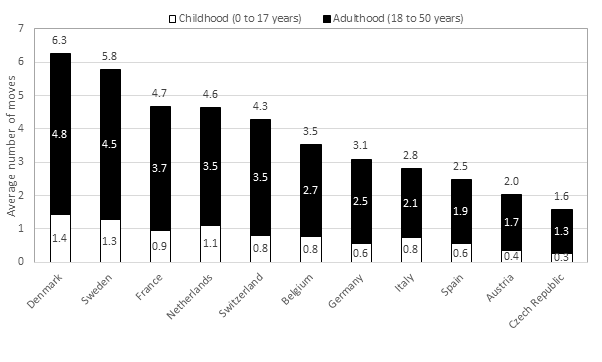

Internal migration levels in European countries Figure 1 shows a marked north-south and east-west gradient, with high levels of lifetime mobility in Denmark, Sweden, France and the Netherlands, moderating southwards and eastwards reaching low levels in Italy, Spain, the Czech Republic and Austria. These results conform closely to the spatial patterns identified in previous comparative studies. Not surprisingly, because relocations in childhood are tied to parents, in countries where adulthood mobility is low so is the mobility of children. In Austria and the Czech Republic, the proportion of child non-movers is above 70 per cent. In contrast, countries at upper intermediate levels of mobility, such as the Netherlands and France, about 40 percent remained immobile, while in the two most mobile countries, Denmark and Sweden, only about a third of children did not move.

Source: Bernard and Vidal (2019), SHARE, wave 3, authors’ calculations

Note: Cohort born 1946-1957. Labels at the top indicate the average number of lifetime moves from birth to age 50. Countries are ranked in order of decreasing average number of lifetime moves

Impact of childhood moves

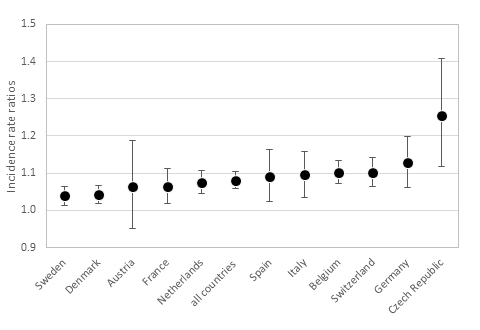

Figure 2 shows that when all countries are modelled jointly, each successive childhood move increase the number of adult moves by 8.14 percent. When models are ran separately for each country, the coefficients remain statistically significant in all countries, except Austria. The effect of childhood moves is particularly pronounced in low mobility countries in the south, east and centre of Europe where moving as a child is less common.

By looking into childhood moves separately by age, we also show that each successive childhood move increases the likelihood to move as an adult in a broadly linear fashion. Our findings also suggest that changing residence in adolescence is particularly influential, but in some countries pre-school relocations have a long-lasting effect on subsequent mobility. This suggests that the very first move in life may exert a particular influence by exposing a child for the first time to the intricacy of moving and the social disruption that it creates, thus having long-term consequences on mobility behaviour.

Source: Bernard and Vidal (2009), SHARE, wave 3, authors’ calculations

Note. Incidence rate ratios are statistically significant at the 0.001 level in all countries except Austria and are reported with a 95 per cent confidence interval.

Implications

Our findings have important implications for future migration trends. A long-term decline in levels of internal migration have been observed in some countries in Europe, North America and Australasia (Champion, Cooke and Shuttleworth 2018). This downward trend means that a decreasing proportion of children are migrating with their parents, with consequences not only in bringing down current migration levels but also potentially in disaccustoming future cohorts to migration in a way that might decrease their likelihood to migrate later in life, thus perpetuating a decline in levels of internal migration. This evolution is likely to be particularly pronounced in low mobility countries which are currently experiencing a migration decline, such as Hungary, Germany and the Russian Federation (Bell et al. 2018), whereas the impact of a downward trends is expected to be weaker in highly mobile countries, such as the Netherlands and Iceland, as our results show that the impact of childhood mobility on subsequent moves is weaker in high mobility countries. This downward trend is by no means universal as some European countries have registered an upswing in their levels of internal migration, both high mobility countries such as Ireland, Norway and Finland, and low mobility countries such as Austria, Belarus, the Czech Republic, Greece and Estonia (Bell et al. 2018). Increased migration among children in these countries could have long-term consequences by accustoming future cohorts to moving in a way that might rise their likelihood to migrate later in life, leading to further increase in migration level in the future, which in turn could reinforce diverging trends in levels of internal migration among European countries.

References

Bell, M., E. Charles-Edwards, A. Bernard, and P. Ueffing. 2018. “Global trends in internal migration.” Pp. 76-97 in Internal Migration in the Developed World: Are we becoming less mobile?, edited by T. Champion, T. Cooke, and I. Shuttleworth. Londong: Routledge.

Bernard A. 2017b. “Levels and patterns of internal migration in Europe: A cohort perspective.” Population studies 71(3):293-311.

Clark, W.A.and W. Lisowski. 2018. “Examining the life course sequence of intending to move and moving.” Population, Space and Place 24(3):e2100

Champion, Cooke T. and Shuttleworth I. (2019) Internal Migration in Developed Word: Are we becoming less mobile? London: Routledge.

About the authors

Aude Bernard is a demographer at the Queensland Centre for Population Research at the University of Queensland, Australia

Sergi Vidal is a social demographer at the Centre for Demographic Studies in Barcelona, Spain

This article is based on

Bernard, A. and Vidal, S. (2019) Does moving in childhood and adolescence affect residential mobility in adulthood? An analysis of long-term individual residential trajectories in 11 European countries, Population, Space and Place, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2286

Leave A Comment