A person’s family structure, i.e., the presence of a partner and the presence and number of children, affects people’s social support networks. Such networks may be especially important when people get older. We study how family structure itself, and the resulting social support networks, are related to older people’s well-being.

For many years, researchers have been interested to identify the relationship between the lives people lead and their well-being, often measured with life satisfaction questionnaires. One aspect of interest regards the association between family structure and life satisfaction. For example, various studies have shown that having a close partner is often positively associated with well-being. On the other hand, studies have also shown that having children is often negatively associated with well-being.

Association between a family indicator (such as having children) and well-being, for example measured through life satisfaction, can be caused by different underlying mechanisms. One mechanism may be that having children causes people to be more or less satisfied with their lives. A different mechanism would be that people who are, or are not, satisfied with their lives decide for or against having children. Both mechanisms can also exist simultaneously.

Our current study does not aim to distinguish between these different mechanisms, thus our results concern associations between different variables; and these associations may derive from all kinds of underlying mechanisms. What interests us is the fact that family structures are often related to certain social network structures, and that these social networks become very important for older people. For example, people with a partner typically experience social support through their partner. People with children will benefit in multiple ways from interactions with their adult children when they grow older. We therefore wondered whether any associations between family aspects and well-being indicators were mainly driven by their role for the networks people have, or whether networks play an independent role. Moreover, assuming that associations between children and well-being indicators are indeed caused by the presence of children and not vice versa (which is not a harmless assumption), we speculated that this effect may mainly be due to the potentially stressful episodes parents experience with younger children that require much support from their parents. In contrast, when parents and children grow older, this relationship may revert, with children becoming a source of social support for their parents.

To answer these questions, we made use of the SHARE data base of older Europeans, perfectly suited for our research questions. Different well-being measures are available for participants, as well as detailed information on their family situation, such as partners, children, and whether these children still live at home. Moreover, these data provide insight into people’s social networks in the fourth round of the data collection (“Wave 4”).

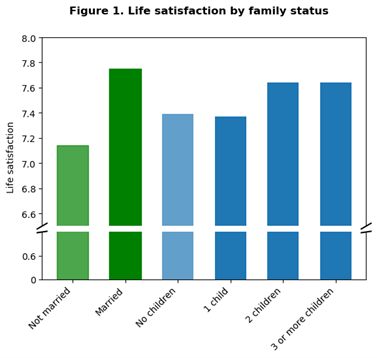

We present some illustrations here for one of our measures, self-reported live satisfaction. In the article we consider different indicators of well-being and mental health. Figure 1 shows raw comparisons of average life satisfaction for different groups: married vs. unmarried, and those with no children vs. those with one, two, or three and more children. These raw averages do not yet control for any other aspects (for example income). However, we see that there seems to be a positive relationship between having a partner, or with having children, and live satisfaction. As we described above, previous studies that found a negative relationship between life satisfaction and children have typically used younger groups of participants. In more detailed econometric analyses of the data we find that there is indeed a positive association between having a partner and well-being. Moreover, we find predominantly positive associations between children and well-being, after controlling for whether the children do still live at home. Consistent with the broader literature, conditional on having children, well-being is lower for those participants where the children still live at home.

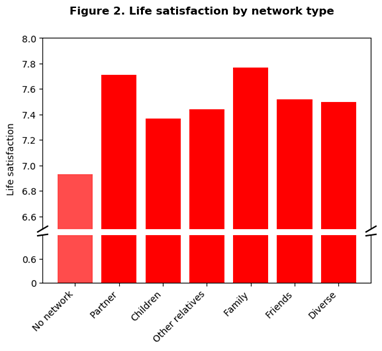

Next, we look at social networks. From the share data we identify different networks that people have, which are named according to their main interaction partners. In the econometric analyses we also control for how large people’s networks are and how often they see members of their network. Figure 2 shows some raw group averages for live satisfaction for people with no social support network versus different groups of social networks.

We observe that there is a positive association of networks with life satisfaction. More detailed econometric analyses show that there is indeed a positive association between well-being and social networks. Most importantly from our current perspective, if we include both the family structure and the social network people have, both are simultaneously associated with well-being. Our results show that both family structure and the resulting social networks are important aspects of the well-being of older Europeans.

About the authors:

Christoph Becker, Alfred-Weber-Institute for Economics, University of Heidelberg

Dr. Isadora Kirchmaier, Alfred-Weber-Institute for Economics, University of Heidelberg

Prof. Dr. Stefan Trautmann, Alfred-Weber-Institute for Economics, University of Heidelberg & CentER, Department of Economics, Tilburg University

This article is based on:

Becker, C., I. Kirchmaier, and S. T. Trautmann (2019). Marriage, Parenthood and Social Network: Subjective Well-Being and Mental Health in Old Age. PLOS ONE 14, e0218704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218704

Leave A Comment